|

Forgiving Parents sort through emotions, search for meaning in son's death ALEC CLAYTON; For The News

Tribune,

April 9, 2004 When asked to write about how I managed to forgive those boys - or if I have

- my initial reaction was to say I had long since forgiven them. From the

beginning, I wasn't so much angry at those boys as the people in their lives

who had taught them to be bigots - the authority figures or parents who

taught them that gays and lesbians were to be despised and beaten for simply

being who they are. But when I discussed my feelings with my wife, she opened my eyes to other

possibilities I had not considered. "I haven't forgiven them," Gabi said, "because they never asked me to." It was true. They never asked for forgiveness. They never said they were

sorry. One of the boys even bragged to the police that given the chance he

would do it again. New and confusing thoughts come up after all these years. Does a person have

to ask for forgiveness before it can be given? Just what is forgiveness,

anyway? The only definition we could find that seemed to apply to our situation was

in the online dictionary Wikipedia en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgive): "A

quality by which one ceases to feel resentment against another for a wrong

he or she has committed against oneself. ... It may be granted with or

without the other asking for forgiveness." That did not clarify my thoughts at all. All I can say for sure is that now,

nine years after Bill's Gabi responded differently. She asked me, "If you feel rage, then have you

forgiven them? Is the forgiveness something you do for you or for them?

Both? And if they ask for forgiveness, is it so they won't have to carry the

deed and the guilt? Don't they have to earn that somehow?" She told me that the one person she had to forgive was herself. "There was

what I saw as an almost natural guilt I had to carry. When Bill committed

suicide, I became a mother who could not keep her son alive. I was then the

one who had failed - I had not done enough, or I had done things I should

not have that contributed to Bill choosing his own early death." I can understand that reaction because I know she processes differently than

I do, but I can't imagine having to live with that guilt every day. Over time Gabi moved from feeling guilt to having regrets. It was at that

time, she says, she was able to forgive herself. Three years before Bill's assault, there was another incident. He was 14 at

the time and he had just come out to us as bisexual. He was raped by a

20-year-old man. For reasons I can't explain, my anger at that man was much

greater than my anger at the boys who beat Bill. He was sentenced to a year

in prison. The boys who assaulted Bill were given 20 to 30 days in juvenile

detention. I felt at the time that all of their sentences were far too

light. Sometimes when I think about them now, I still feel the rising rage. But

mostly I just hope they learned from their mistakes and will never repeat

their crimes. More important, I hope the lessons we all learn from such

experiences will eventually change the climate of hate that spawns such

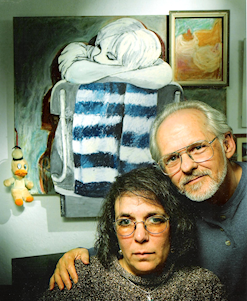

crimes. Editor's note: Alec Clayton is a former editor in the SoundLife section who

writes the biweekly community theater column in GO. Nine years ago, his son,

Bill, committed suicide shortly after being beaten in an attack that police

labeled gay bashing. Alec, an Olympia resident, shares his struggle to

forgive the young men, whom he holds responsible for Bill's death. |