|

Portrait of the

artist as an aging man

Exhibition at

the Washington State Convention Center,

Seattle, 2009,

with my wife, Gabi

In my graduate theses written

in 1970, I argued that traditional art created as an aesthetic object to be set

on a pedestal or hung on the wall is a dead tradition and therefore painting and

sculpture as we know it is obsolete. In defense of my thesis, I refused to hang

the required graduate exhibition (which took a lot of persuasion). And like my

hero at the time, Marcel Duchamp, I retired as an artist. I went into the

newspaper business and did not paint another picture for something like 15

years.

I edited a weekly newspaper in New York for about five years. Over the next

eight years (in partnership with my wife, Gabi) I published a weekly newspaper

and an arts quarterly in Mississippi. I wrote art reviews and taught painting

and drawing part-time for the University of Southern Mississippi. So much

contact with art eventually enticed me into trying my hand at it once more, so I

started painting again in 1985. Since getting back into painting I have tried to keep active with both

literary and visual arts.

... Bumps along the road

Moving to New York in the

early ‘70s, I quickly got involved with a wonderfully strange organization

called

Everything For

Everybody. We were a personal service organization which

fed the hungry and housed the homeless and helped people find jobs and

—

in

short —

everything for everybody. The organization was run by volunteers who

worked without pay, living communally and eating the same food we scrounged for

the street people and wearing the donated clothes that we gave away. At any

given time there were anywhere from seven to a dozen staff members. We worked

around the clock, sleeping in shifts. We also published a weekly newspaper, and

my main job was editing the paper.

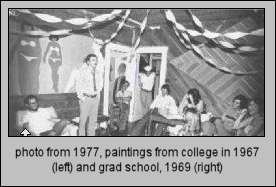

There I met Gabi. We fell in love. Two idealistic hippies out to save the

world. We got married in a beautiful ceremony held in the basement. We wrote our

own vows (and no, it was not a legal wedding). Everything was donated, from the

wedding cake to the ring.

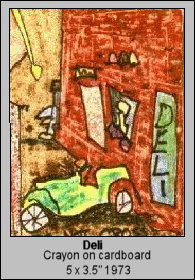

This was during my

"retirement" from painting. While it's true that I didn't paint during

this period, I did

buy a box of Crayola crayons and made hundreds of little crayon drawings, which

I gave away. I gave one called "Deli" to Gabi before we were married.

It's the only one we still have.

This was during my

"retirement" from painting. While it's true that I didn't paint during

this period, I did

buy a box of Crayola crayons and made hundreds of little crayon drawings, which

I gave away. I gave one called "Deli" to Gabi before we were married.

It's the only one we still have.

In 1977 we headed south to my hometown, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where

we started a branch of Everything For Everybody. The day we opened for business,

the police shut us down because we did not have a license (and the city wouldn't

approve a license). So we started a weekly newspaper with no staff, next to no

money, and equipment consisting of an IBM Selectric typewriter and a pot of

rubber cement. Gabi and I wrote all the articles, did the art work, sold ads,

distributed the paper, etc., etc., etc. The paper was called Persons.

Eventually it grew. And we formed a non-profit corporation and started

housing the homeless and serving food to the poor and essentially doing all the

things we’d done in New York. We lived on ad revenue and donations, always

well below the poverty line.

We celebrated our 10th

wedding anniversary during this period. This time with another

wedding, a real one with a license and everything (we made it legal at last). Our children, ages 6 and 8, stood by us as we said "I do," and then our youngest, Bill,

ran outside and jumped into the wading pool fully dressed in his new clothes. We celebrated our 10th

wedding anniversary during this period. This time with another

wedding, a real one with a license and everything (we made it legal at last). Our children, ages 6 and 8, stood by us as we said "I do," and then our youngest, Bill,

ran outside and jumped into the wading pool fully dressed in his new clothes.

I was a native, and I had graduated from the local university. Gabi, on the

other hand, was New York born and raised in Puerto Rico, New York and San

Francisco. My roots were Southern Baptist; hers were New York

Jewish-atheist-radical. To put it mildly, we didn’t exactly fit in. People

called us Communists. One preacher gave a sermon about how we were taking men’s

property away from them because we sheltered battered wives.

It was tough. After a few years we burned out. We were emotionally and

physically exhausted. We shut down the shelter and replaced the weekly newspaper

first with a monthly magazine, and later a quarterly called Mississippi Arts

& Letters, and I started teaching part-time at the University of

Southern Mississippi. That was when I started back painting.

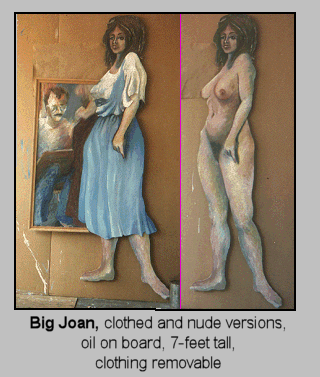

... Too naked

At first I made figurative

paintings that were a kind of hybrid between pop art and surrealism. They were

pretty awful. A local gallery refused to show some of my nudes because they were

too —

well, naked. In response, I started making cut-out figures on Fomecore

and wood that were like old fashioned paper dolls, naked, but with clothes that

could be put on and taken off.

Thornton Willis, an old friend and a successful painter in New York, was

invited to show in the university gallery and he introduced me to oil sticks

which were something new in the market then. I immediately fell in love with

them. They’re like the ultimate crayon. With oil sticks you can combine the

best elements of drawing and painting as well as the best characteristics of

acrylic and oil. I’ve been using them ever since, sometimes mixed with other

media.

The magazine we published was a

critical success but a financial disaster; my job at the college was only

part-time, and we were tired of the South. So, in the summer of 1988 we headed

west. Packed our kids and everything we owned in a U-Haul trailer and drove to

Olympia, Washington. I got a job first at B Dalton selling books and later

writing for a newspaper in Tacoma where I worked until 2001. The magazine we published was a

critical success but a financial disaster; my job at the college was only

part-time, and we were tired of the South. So, in the summer of 1988 we headed

west. Packed our kids and everything we owned in a U-Haul trailer and drove to

Olympia, Washington. I got a job first at B Dalton selling books and later

writing for a newspaper in Tacoma where I worked until 2001.

I continued painting

figurative works but gradually lost interest in that and started doing more

abstract paintings. The abstract paintings, beginning in 1990, were pure

abstract expressionism. At last, I was really happy with my art. The sheer

sensual pleasure of making energetic, gestural marks was exhilarating. But it

did bother me that I was working in a tradition that had been out of favor for

thirty years.

... finding my vision

When “accused” of not painting from nature, Jackson Pollock retorted,

“I AM nature.” A somewhat arrogant statement but very descriptive of the way

he worked. Pollock said he always started out spreading paint with no particular

image in mind during what he called a getting acquainted period. I work in much

the same way, letting the work evolve in an organic way and finding the forms on

the canvas as I work. I usually begin, like Pollock, with a getting acquainted

period, layering and scraping the paint in random ways until I begin to see

forms emerge. Then I begin to develop those forms. I listen to the painting as I

work and it tells me what to try next; if what I try doesn’t work, it tells me

to scrape it off or paint over it and try something else.

While I believe my work differs

from abstract expressionism in important ways, there are obvious influences, and I am very much indebted to people like Pollock and de Kooning and

Motherwell for teaching me how to paint. The ways in which I believe I differ

from these and later abstract painters coming out of the same tradition are two

fold.

First, I create

definite images which are enclosed by edges, which means they look like objects

or figures on a ground as opposed to the geometric forms and free flowing

brushstrokes of most abstract art. I think of these forms as invented creatures

that mimic the movements or living creatures. Sometimes viewers see animals or

body parts, but such references to nature are usually not literal.

The second difference is that I use a much greater range of

hue and value than is generally employed in abstract painting. And I use

patterns such as stripes, checks, zig-zags and dots, which earlier

abstractionists never used. Sometimes what I like to do is throw in

“everything but the kitchen sink” and make it as confusing and harsh and

jarringly ugly as possible, then try to find ways to bring it all together into

a harmonious whole. I guess that brings us to the bottom line, which is that I

am a very traditional painter in the modernist tradition.

Over the next decade, my development was gradual, slowly finding forms within

the gestural framework that were my own. Figures, or parts of figures, continued

to show up, but over the years they began to give way to invented forms that may

relate to human figures or animals or other organic forms, but the direct

references have gradually gone away. In the earlier abstractions, the forms were

all amorphous, not well defined, just interwoven marks and shapes with no

defined figure or ground. The later works have more clearly defined forms with

definite edges and clear distinctions between figure and ground. That change

came about when I did an installation for Childhood’s End Gallery in Olympia.

It was a site specific work titled "Rhythms in Evolution," consisting

of one long and skinny, scroll-like painting that stretched around 75 feet of

gallery wall. Hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the gallery were similar

paintings on wooden panels. The 75-foot long painting, by the way, I sold by the

foot. People could pick out sections and after the show was over I cut them out

and framed them. Since

the mid '90s I have continued to paint, going back and forth between

abstract and figurative painting.

I

had heart surgery in 2002 and during a prolonged recuperation period I did not

have the energy to paint. Sitting in front of a computer took much less energy,

so I began experimenting with computer-manipulated images, scanning some of my

old figurative paintings and manipulating them in a paint program. (Some of

these works can be seen

here.)

Increasingly since that time I have spent less time painting and

more time writing.

Note: this was written in 2009.

I have not painted since then. See

"I Dreamed a Dream of

Painting."

copyright © Alec Clayton 2012 |

![]()