by Alec Clayton

My dad died 35 years ago, and my mother died 38 years ago. This week I received in the mail a large box of family memorabilia from Pat Parish Ackland, one of my many nieces. Inside were photographs, more than half of which were of people I don’t recognize, and newspaper clippings, my dad’s 8th grade report card, and many letters to and from family members—including at least one of the letters my parents wrote to each other on their wedding night—love letters written to each other while sitting in the same hotel room. Perhaps the most romantic thing I’ve ever heard of.

Mother got lung cancer in the final year of her life, and while being treated for cancer, it was discovered that she might have had a brain tumor. It affected her thinking so that she was not always in touch with reality—or so I was told. I never saw evidence of this until the last day of her life. She was in the hospital, and I was visiting with her. She thought she was on a ship heading to Hawaii, and she complained about the food. The nurses told me not to let her get out of bed and walk without a nurse. But she did get out of bed, and I tried to stop her. I put my arms around her waist, and she said, “Do you want to dance?” And so I danced with my mother to imaginary music in the hospital room/cruise ship on the way to Hawaii. She died later that night.

At some point after her death, my father wrote the following memory of her:

“About 2:30 a.m. I woke to go to the bathroom as usual. When I went back to bed, she was not there. I turned on lights and started looking for her. She was at the front door turning the light off and on. As soon as she saw me, she started saying, ‘I am not going back there.’ She was frightened and refused to go back to bed; she thought someone in this house was trying to hurt her, and she kept trying to get out the door. I tried to calm her but could not break her grip on the doorknob. She said she was stronger than me and proved it. After an hour, I was exhausted, and I called an ambulance. She agreed to go in the ambulance to the hospital.

“Dr. Felts ran all kinds of tests. He thought the tumor had moved to her brain but on the scat test only a blood clot showed up, and he said that was an old one. He called in Dr. Roberts, who is a brain doctor. He said today that results from all the tests are not in yet, but he thinks it’s a stroke. At times she seems normal, but at other times she cannot tell reality from fantasy. That trouble with her hair (I don’t know that he was referring to) was the result of chemicals used on her brain, but she thinks some kids did it.”

After Mother died, Dad spent many days writing a memoir. His hands were severely cramped and gnarled from arthritis, and he could barely type. It must have been a terrible physical ordeal, but mentally and emotionally I believe writing that helped him cope. Gabi and I were scheduled to move to Olympia, Washington. She was already registered at The Evergreen State College. We felt bad about leaving Dad but knew there was other family to take care of him. After we left Mississippi, he went to live out the remainder of his life with Lynda, the youngest of his three daughters, in Saltillo, a tiny town near Tupelo, where our family had lived for much of our lives.

He wrote the following shortly before he left to live out his final years with Lynda:

“I’ve lived in this home for 34 years, longer than any other house in our memory. This house is home, it is full of pleasant memories, and Mother is all over this house. I feel her presence all the time; I cannot bear the thought of leaving it. There are six families on this street that are my friends and look out for me as if I were one of them. All the wives are at home most of the time, none of them work, so it is not very probable that all six would be gone at any one time. Three of them are on my Lifeline and have keys to my front door, so they may enter if I should be unable to open the door in an emergency.

“Being on Lifeline, I do not have to give anyone directions to get here or tell them what is wrong. All I have to do is press a button, and the hospital knows I need help. Neighbors bring me plate lunches often, which is a welcome change from the Meals on Wheels. In addition, there are several delis here where I can buy most any food that I may desire. I do not know anyone still living in Tupelo and am too old and tired to make new friends. I have had a few thoughts about buying a trailer, but from what little I know of trailer living, I would rule that out. I cannot bear the thought of being cooped up in a trailer.

“The only advantage I can see in moving would be that Lynda would be close and could look after me as Alec has been doing. Mother and I discussed death several times after we discovered that she had cancer. Neither of us wanted to become dependent on any of our children or anyone else. I am able to take care of myself, and if I do become so weak and senile that I need help, I think the only thing would be a nursing home.

“I have everything here handy and do not want to have to arrange same for somewhere else. I may be crazy, but I am happy in this house with my memories and my wife, a spirit.”

There was one other thing in that box of memorabilia that I would like to share, at least in part. It is a letter I wrote to all of my siblings a year after we moved to Olympia. I wrote:

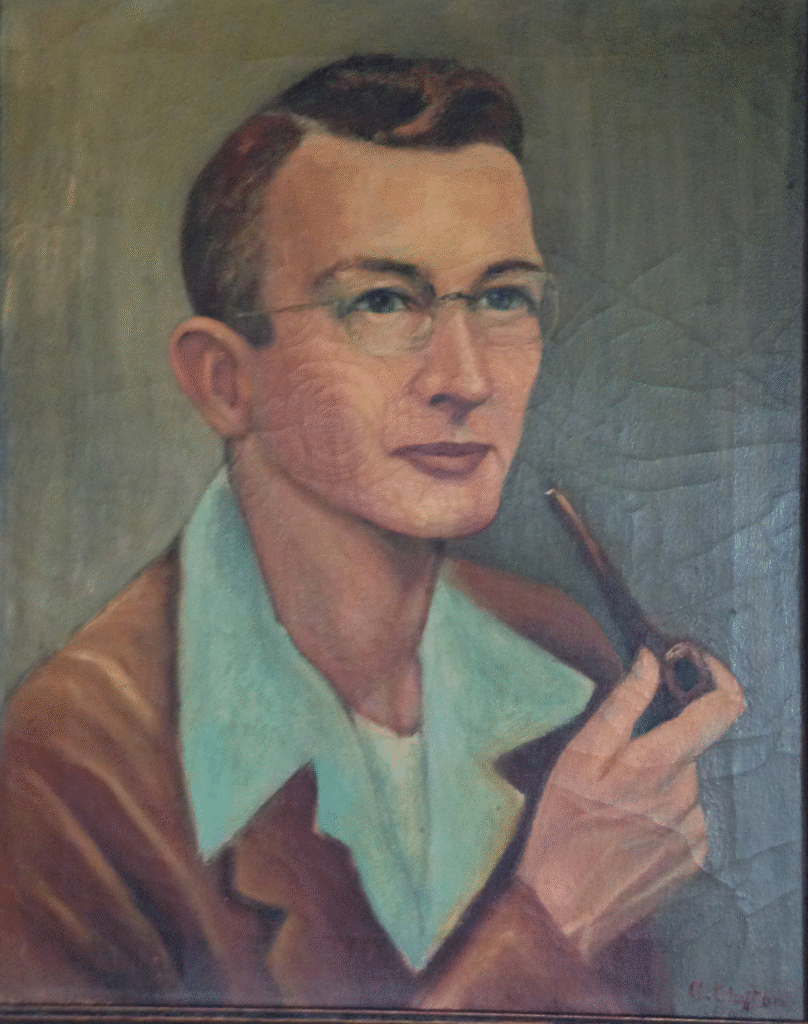

When I think about Daddy, I picture him as he was twenty years ago: irreverent, strong, full of humor, gleefully getting Mother’s goat. Boy, did he know how to push her buttons. I remember the spark in his eye as he tussled with a lapful of grandchildren in that saggy old recliner that had been reupholstered many times. I picture him in a fishing boat, a cigar clamped between his teeth. It’s almost inconceivable but true that Gabi and Bill and Noel never knew him the way he was back then. They never heard his normal voice (his voice box had been removed). I couldn’t remember his normal voice either, but then one day I heard a recording of him, and I was surprised to hear that he sounded just like me.

Daddy was never demonstrably affectionate. I can’t remember him hugging me more than twice. In the hospital, when he had his first heart attack—Mother was still alive then, but she was not in the room—Daddy strained to say something to me. He could barely make a sound, and I couldn’t understand him. I had to make him repeat himself two or three times. Finally, I heard what he was trying to say. It was, “Give me a hug.”

Beautiful