My wife and I have told this story a gazillion times. But maybe you missed it.

My wife and I have told this story a gazillion times. But maybe you missed it.

It was the fall of 1973. I was working at a social service organization called Everything for Everybody. We accepted donations of all kinds of things that we gave away, we had a soup line every afternoon at 4 o’clock, we helped people buy, sell and swap things—a kind of Craig’s List before there was a Craig’s List. And we were a hangout for a whole bunch of crazy, loving people.

EFE, as we called it, was on West 13th Street in Manhattan, which at the time was the heart of the meat packing district. At certain times of the day, there were animal carcasses swinging from hooks on conveyor belts right near our front door. At other times, when the markets were closed—they conducted their business mostly in the early morning—the street was so empty could we set up a volleyball net and play in the street. Inside there was a wall of shelves to the left, the donated clothing we gave away, and a diner-style counter to the right where our members ate and drank endless cups of coffee and helped prepare the soup for the street people—the brothers, as we called them, even though there were also a few women. Behind the long, narrow front room was a room where we stored food for our members and the brothers and the food co-op we operated. Behind that was another room where we put together the newspaper we published and where the live-in staff slept. At that time, the staff was me and one other person. I edited the newspaper, and the other person did most of the cooking.

One day a woman named Naomi came in. She spent the afternoon with us, chatting, drinking coffee, helping chop vegetables for the soup. I told her we were having a party in our basement entertainment area that night and said she should come. She asked if she could bring her daughter.

“Sure,” I said.

She looked me in the eye in a most challenging way and said, “She needs a man.”

Well, the daughter showed up for the party that night, but the mother didn’t. The daughter and I hit it off immediately. It was shortly before her twenty-first birthday. We stayed together that night, sleeping on big throw pillows on the basement floor, and she never left except to go home and pack up some of her things. She dropped out of college, quit her part-time job, joined the staff of Everything for Everybody and moved in with me.

That summer we were married in the most informal and delightful of ceremonies. Gabi was driven to the wedding in a rickshaw. Our boss, Jack, officiated. We wrote our own vows, which seem very pretentious and new-agey when I read them now, and we said them under an arch gazebo someone had donated. We did not bother with a marriage license, and Jack was not licensed to perform weddings. He began the wedding by saying, “Alec, our chronicler of events, and Gabi, our earth mother . . .”

That summer we were married in the most informal and delightful of ceremonies. Gabi was driven to the wedding in a rickshaw. Our boss, Jack, officiated. We wrote our own vows, which seem very pretentious and new-agey when I read them now, and we said them under an arch gazebo someone had donated. We did not bother with a marriage license, and Jack was not licensed to perform weddings. He began the wedding by saying, “Alec, our chronicler of events, and Gabi, our earth mother . . .”

After the vows were said and Jack pronounced us husband and wife, everyone danced in the street.

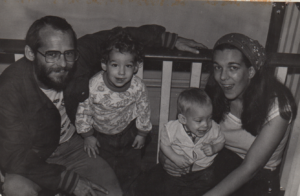

Ten years later, with our sons standing with us, we made it legal. We got married again. In our house with a license and an Episcopal priest officiating. Twenty-five years after that second wedding, our oldest son built an exact replica of that arch gazebo, and he and his wife stood under it to say their vows. This summer we’ll celebrate our forty-sixth anniversary.

I was never particularly crazy about Naomi, but I’m glad she told me her daughter needed a man.